After its arrival in the UK from British Columbia in the early-Spring of 2004, our Catalina, then still registered in Canada as C-FNJF, continued to fly in its yellow, red and green livery.

These colours had been applied some years ago by the Province of Saskatchewan who had operated it, and two other Catalinas, in the water bombing role, fighting forest fires. Although it was intended to repaint the aircraft in a wartime scheme, there was no opportunity to accomplish this during 2004 as it was too busy flying at air shows! The unusual colours were, however, the subject of much interest to air display visitors and a few even hoped it might remain in those colours. However, the owners had different ideas!

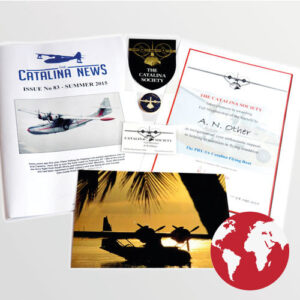

Our Catalina in the 8th Air Force Colours of 44-33915 landing at Rougham in the Summer of 2005. Photo: John Allan.

Most air show organisers prefer ex-military aircraft, or ‘warbirds’, to be painted in a military scheme and there are few around that have operated in commercial schemes. So, in order to gain bookings, Plane Sailing needed a distinctive livery. Our previous Catalina had operated in two military schemes, the first representing 210 Squadron’s JV928/Y in which Flt Lt John Cruickshank earned his Victoria Cross and the second a Canadian Canso A. The latter aircraft commemorated Canso A 9754/P of 162 (BR) Squadron, RCAF, the aircraft involved in the action following which Flt Lt David Hornell was also awarded the Victoria Cross, although, sadly, his award was posthumous. The reason for choosing the latter scheme was that it was white overall which suited the operational requirements for our Catalina. Being basically white, it could be adapted to carry sponsors logos or liveries if the need arose and these could then be temporarily sprayed over with white paint, removable when required. This flexibility served Plane Sailing well when operating its first Catalina in the 1980s and 1990s and became a logical step forward for our new aircraft, by now registered G-PBYA. But which scheme to use?

Initially, it was thought that G-PBYA would be painted as Hornell’s aircraft, like our previous ‘Super Cat’ but this may have caused some confusion. Firstly, our old aircraft is still extant at Lee-on-the Solent, albeit dismantled and nowhere near flight, and some people may have thought it was airworthy again in the same colour scheme as before. Secondly, since the accident that befell our old aircraft, the Canadian Warplane Heritage have re-painted their own airworthy former RCAF Canso A as Hornell’s aircraft and it was felt that having two Cats flying in the same colours, even if on opposite sides of the Atlantic, would be confusing.

So, the search was on for another overall white livery and your Editor did some digging with surprising results. Having hit on an idea, I consulted with Ragnar Ragnarsson who was able to provide not only a photograph of the original aircraft but a copy of the incident report that described its demise. Ragnar had originally received these from Billy DeMoss whose stepfather is John V. Lapenas, Jr., the son of J.V. Lapenas whose role in this story will become evident. Add to that the fact that the featured aircraft had an East Anglian connection and was white all over and it did not take too much lobbying to persuade Paul Warren Wilson to give the idea his blessing! So, in early-June, G-PBYA was transformed into a United States Army Air Force OA-10A Catalina, serial 44-33915, as operated by the 5th ERS (Emergency Rescue Squadron), 8th Air Force from Halesworth in Suffolk in early-1945!

The original 44-33915 was built by Canadian Vickers at Cartierville, Quebec with the construction number CV-400 and the designation OA-10A-VI, the VI suffix denoting that it was built by Vickers as opposed to earlier USAAF machines built by Consolidated that had the designation OA-10A-CO. In due course, this Catalina found its way to the United Kingdom where it joined the 5th ERS at Halesworth.

The background to the USAAF operating Catalina amphibians in the UK was as follows. The USAAF had used Catalinas for air-sea-rescue work in the Mediterranean but had relied on RAF aircraft to rescue downed airmen around the UK’s east coast. However, the Americans wanted to use their own aircraft in the North Sea and so, in August, 1944 General Spaatz requested that Catalinas be provided for the 8th Air Force. Some delay ensued but, eventually, six OA-10As were ordered to the UK under Special Order 223 dated December 9th, 1944 from the US Army Air Force HQ at Keesler Field, Mississippi. The Catalinas were delivered by the South Atlantic route from Keesler AFB, Biloxi, MS through Morrison Field, West Palm Beach, Florida and on via Puerto Rico, Trinidad, Dutch Guinea, Belem and Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, Ascension Island, Roberts Field in Liberia, Dakar, Marrakech and an unknown airfield in Cornwall with the first four arriving at Bovingdon on January 17th, 1945. Two further aircraft were delivered a few days later. The six were serialled 44-33915 to 44-33917, 44-33920, 44-33922 and 44-33923. After being evaluated, all six Catalinas were flown to Halesworth where they were to be based for their ASR work. However, before they could enter operational service, they had to be modified and this work was carried out at Neaton in Norfolk. The Canadian radio equipment was removed and replaced with SCR-274N Command and SCR-287 Liaison radios, and SCR-269 radio compasses and AN/AIC-2 interphone equipment were substituted for the original fittings. In addition, the SCR-521 radar was removed and replaced by AN/APS-3 sea search radar and SCR-729 Rebecca equipment. The driftmeter and all armour plating was stripped out, the flooring around the blisters was modified to ease access for rescued airmen and some hull glazing adjacent to the navigator’s position was plated over to prevent glare. Stewart-Warner heaters were installed to make rescued crews more comfortable once inside the Catalinas and some modifications were carried out to the bomb aimer’s position, sea anchor and control locks. All of these modifications inevitably led to a delay in the six Catalinas entering service and operational flights did not commence until the end of March 1945.

In due course, further OA-10As were received at Halesworth in the form of 44-33987, 44-33991, 44-33995, 44-34003, 44-34005, 44-34013, 44-34017, 44-34028 and 44-34067. Another OA-10A that may have operated with the 5th ERS was 44-33913.

The 5th ERS had previously operated from Boxted as the Air Sea Rescue Squadron, 65th Fighter Wing, Detachment B having been formed in May 1944 with a complement of war-weary P-47D Thunderbolts equipped with dinghy packs and sea-marker equipment. At the beginning of 1945, the squadron had been re-named the 5th ERS and moved to Halesworth where it continued to fly P-47s in addition to its new Catalinas and B-17s. So it was that 44-33915 was operating over the North Sea on March 30th, 1945 on a mission that was to prove its last and which, sixty years later, was to be commemorated by our own airworthy Catalina!

A rare photo of the original OA-10A Catalina 44-33915

As mentioned earlier, our Society member Ragnar Ragnarsson had already carried out some research and had a copy of the Air Sea Rescue Mission Report for the events that were to end in the demise of 44-33915 and he happily supplied a copy when he discovered that, coincidentally, I was also researching the same event! The report is reproduced in full below.

It is dated April 10th, 1945 and was compiled for the Headquarters, 5th Emergency Rescue Squadron by the captain of 44-33915, 2nd Lt John V Lapenas. His aircraft’s callsign for the mission was Teamwork 75. The type of mission was quoted as Patrol, Search and Rescue Attempt, the dates covered as 30th March to 5th April, the time mission start as 12.25, the position 53-31N, 06-12E, the conditions hazy and the number of other aircraft involved 2, possibly 3. The report continues as follows:

“March 30th: Took off at 1225 and proceeded to patrol area ‘B’ for Baker. In position at 1245 and notified Colgate. At 1430, was instructed by Colgate to proceed to position 53-27N, 03-46E where Teamwork 71 was down and in trouble (Teamwork 71 was another 5th ERS OA-10A Catalina, serial 44-33917 – Ed.). Over Teamwork 71 at 1500 and started circling; a Warwick was already circling Teamwork 71. Attempted to find out his trouble by V/X and R/T and W/T with nil results. Teamwork 71 instructed us to ‘stay up’ by V/S. No attempt was made to land due to high seas. At approx 1700, Colgate relay informed us that fighter escort (P-51s) of two ships will rendezvous at our position over Teamwork 71 to escort us to fighter pilot in dinghy at 53-31N, 06-12E which was approx 3 to 5 miles off the Dutch Island of Schiermonnikoog. At approximately 1800, Teamwork 74 arrived to relieve me. At approx 1825 my escort of two P-51s arrived and we proceeded for the aforementioned position. Arrived over the area at 1855. It was getting dark, vis was very poor and did not sight dinghy until flares were sighted. Sighted and lost dinghy twice in process of getting ready for landing. Landed at 1905 in a sea of approx six feet. Man in dinghy was sighted approx 100 feet of starboard side and to the rear. Attempted to turn around but discovered my starboard engine was dead. Further inspection showed that the oil was pouring out. Sea anchor was put out to facilitate turning but the wind was strong and we kept weather cocking into it. Attempted to drift back to dinghy but darkness had settled and we lost sight of him. An inspection was made of the ‘ship’ and the findings were six rivets out in the navigator’s compartment. After landing on the water the engineer noticed an immediate drop in oil pressure on the starboard engine and the oil pouring out. Soon after the engine froze. He was unable to contact me due to my conversation with the P-51s on VHF. Immediately on finding my engine out I notified my escorts to tell Colgate I was in trouble and unable to take off. Radioman sent out an SOS on the W/T and tried to destroy radio equipment in event of capture. Started left engine and taxied for 1 ½ hours on a heading of 320 degrees to get further away from the shore. Kept radio silence throughout the night. Sea calmed down some but around 0300 it picked up again. All members of crew got sea sick except pilot. Diagnosis of engine was that one of the main oil lines had burst and the oil had leaked out completely. Hull was sound except for small leak in the navigator’s compartment.

March 31st: At 0750, sighted two Warwicks and 3 P-51s and fired red flares. VHF contact was made with fighters but receiver went out shortly (after) and was only able to transmit. At 0900 lifeboat was dropped. The drop was excellent. Attempted to bring the lifeboat alongside ‘ship’ but sea was rough and the lines kept breaking in our attempt to get it alongside the plane. The lifeboat began to break up due to contact with our plane. Radio started working again. NOTE: at approx 1150, a P-51 aircraft notified us in the clear that we would be without cover for approximately ten minutes. In eight minutes, they were back and notified me. At 1200 hours, two ME210s (sic) came out of the sun at approx 500 feet and strafed our plane, making two passes. The tail was completely shot off, the port float practically shot away and the port wing damaged. Numerous holes were in the plane and it started to leak profusely and settle in the water. The left float gave way and the plane listed to port. The co-pilot claimed he saw a Me109. No one was injured in the strafing. We proceeded to abandon ship taking with us all emergency equipment and supplies possible.

This amazing photo, although of poor quality. Note the badly damaged tail.